By Nick Faris and Guy Spurrier

Brad Gushue had reason to be ruffled. It was last Wednesday in Regina, and the Team Canada skip had just suffered his first loss at the Brier, a 10-7 defeat to Brendan Bottcher of Alberta. His team had already assured itself a spot in the next round, but missing out on an undefeated record in pool play had to sting.

When reporters approached him for post-game comment, though, Gushue saved his strongest words for another matter: the tournament’s new 16-team format.

“The more I play it, the more I hate it,” he said. “I don’t like it at all. It’s a terrible format. I’m not going to mince words.”

Gushue’s complaints were indicative of the ire Curling Canada received from some corners over structural changes it made to this year’s Brier and Scotties Tournament of Hearts. Where previous national championships were contested by 12 teams, the 2018 events featured 16, ensuring every province and territory — plus the defending champions and a wild-card team — was represented in the main field.

The concern was that the focus on inclusivity would blight the quality of play in the round robin. Weaker teams such as Nunavut and Yukon, which used to disappear before the main draw started after failing to win a four-team pre-qualifying pool, would now get to stick around for seven games just to get pasted by legitimate contenders.

Now that each tournament is over — Jennifer Jones won the Scotties last month and Gushue beat Bottcher in Sunday’s Brier final — it’s worth investigating whether this fear came to fruition. Were the 2018 round robins actually less competitive than those of past three years when the field was winnowed with the qualifying draw?

We collected the end-by-end scoring data for the last four years of Briers and Scotties tournaments to compare. We looked at only round-robins matches, when the maximum number of teams were competing.

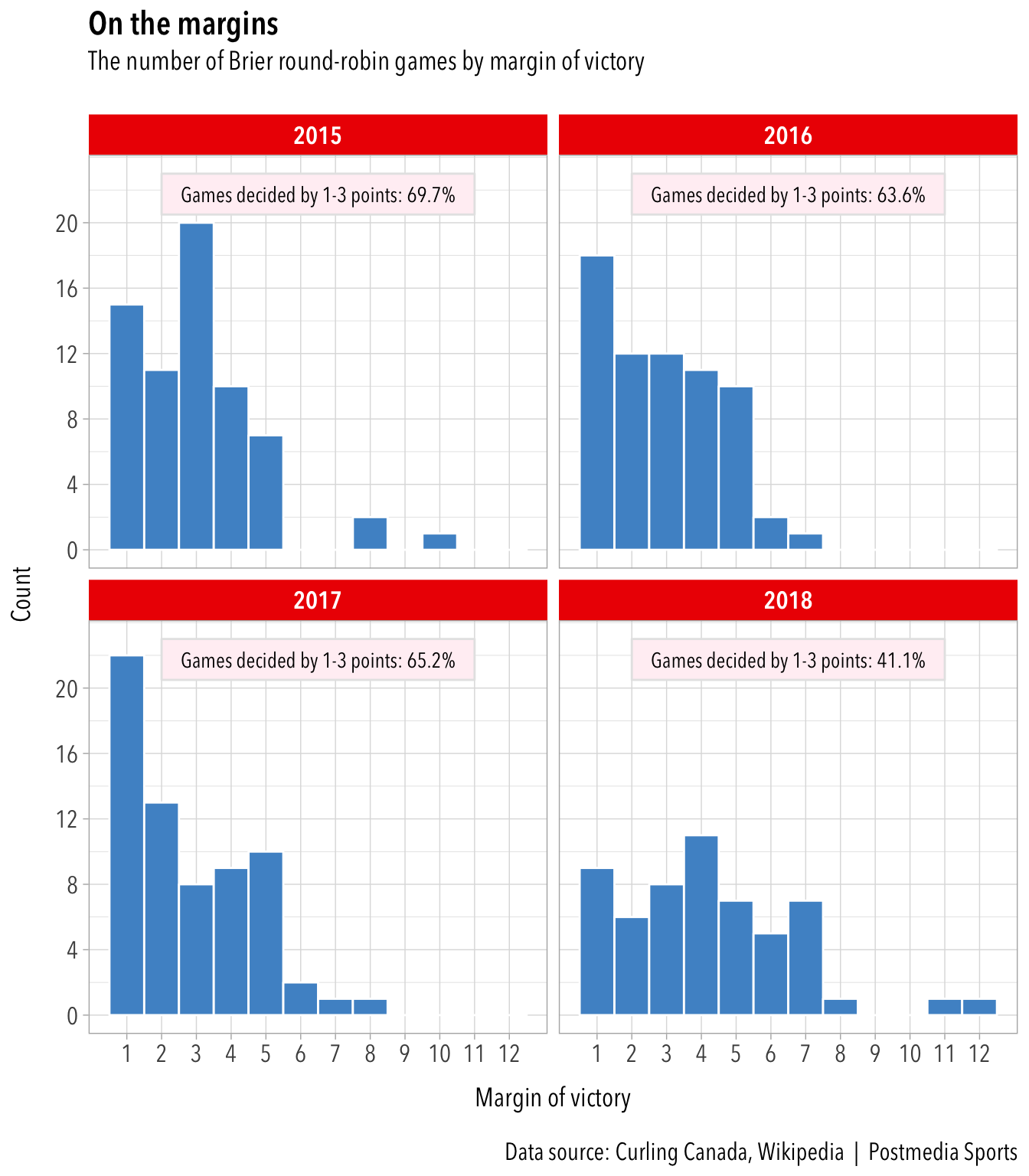

One way to quantify quality of competition is through margin of victory. You would expect a less-competitive tournament to have more blowouts.

This year’s Brier round robin had far fewer close games than the previous three tournaments: only 26.8 per cent were decided by one or two points, compared to an average of 46 per cent in the other three years charted above. By the same token, there were a lot more blowout victories: 58.9 per cent of games were won by four or more points, well up from a three-year average of 33.8 per cent.

Ten of this year’s 112 games were won by seven or more points, compared to six of 396 in the past three years. This Brier also featured the two biggest routs: Nunavut’s 14-3 loss to Ontario and its 14-2 spanking at the hands of P.E.I.

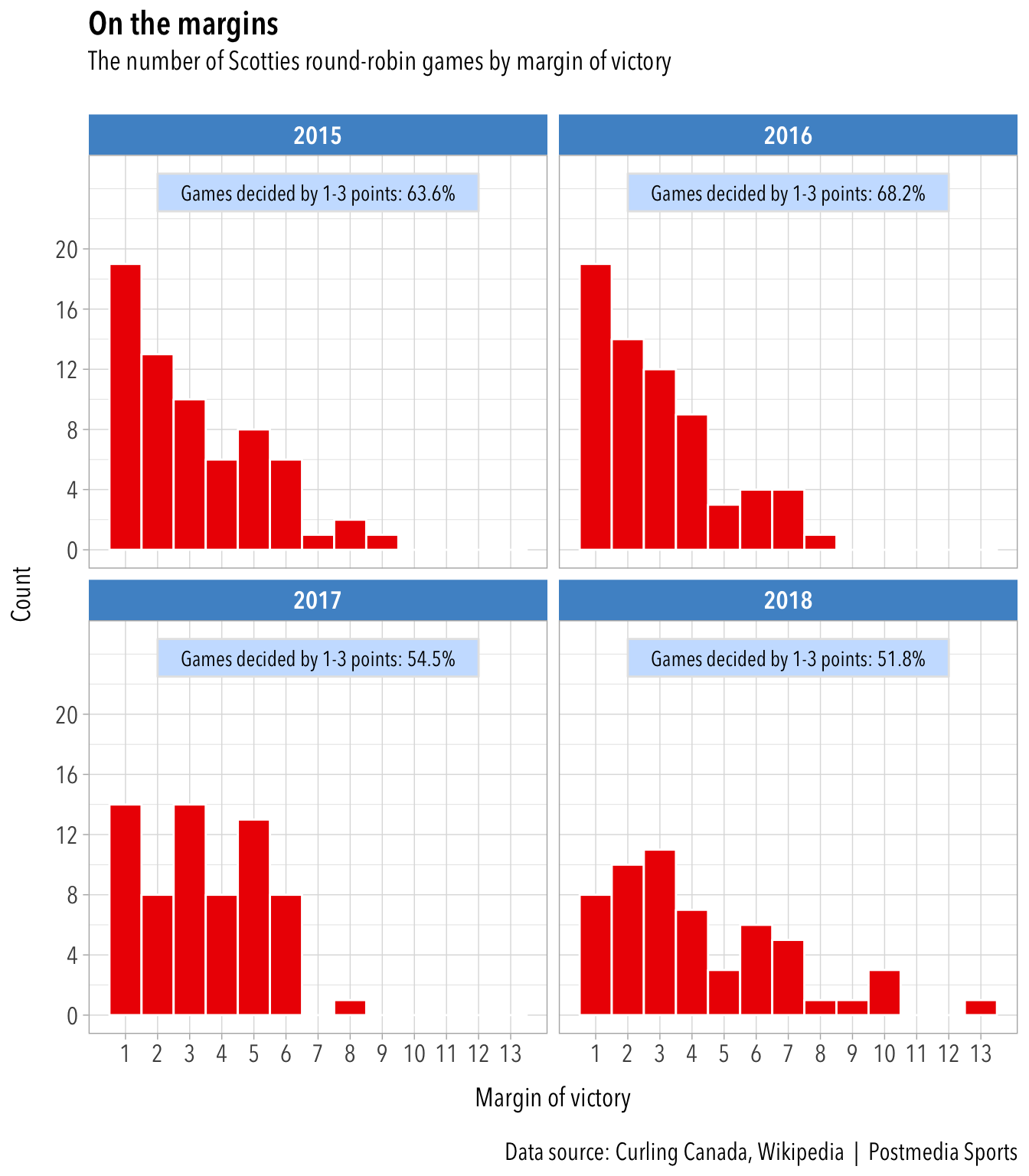

Here’s a margin of victory chart for the Scotties.

There were consistently few huge blowouts of seven points or more before 2018, when 19.6 per cent of the round-robin games fit that definition (the previous three-year average was 5.1 per cent). Particularly egregious were the three games decided by 10 points — Manitoba over the Northwest Territories, Ontario over Nunavut and Alberta over B.C. — and Manitoba’s 14-1 win over Yukon. In no other year was there even one double-digit win.

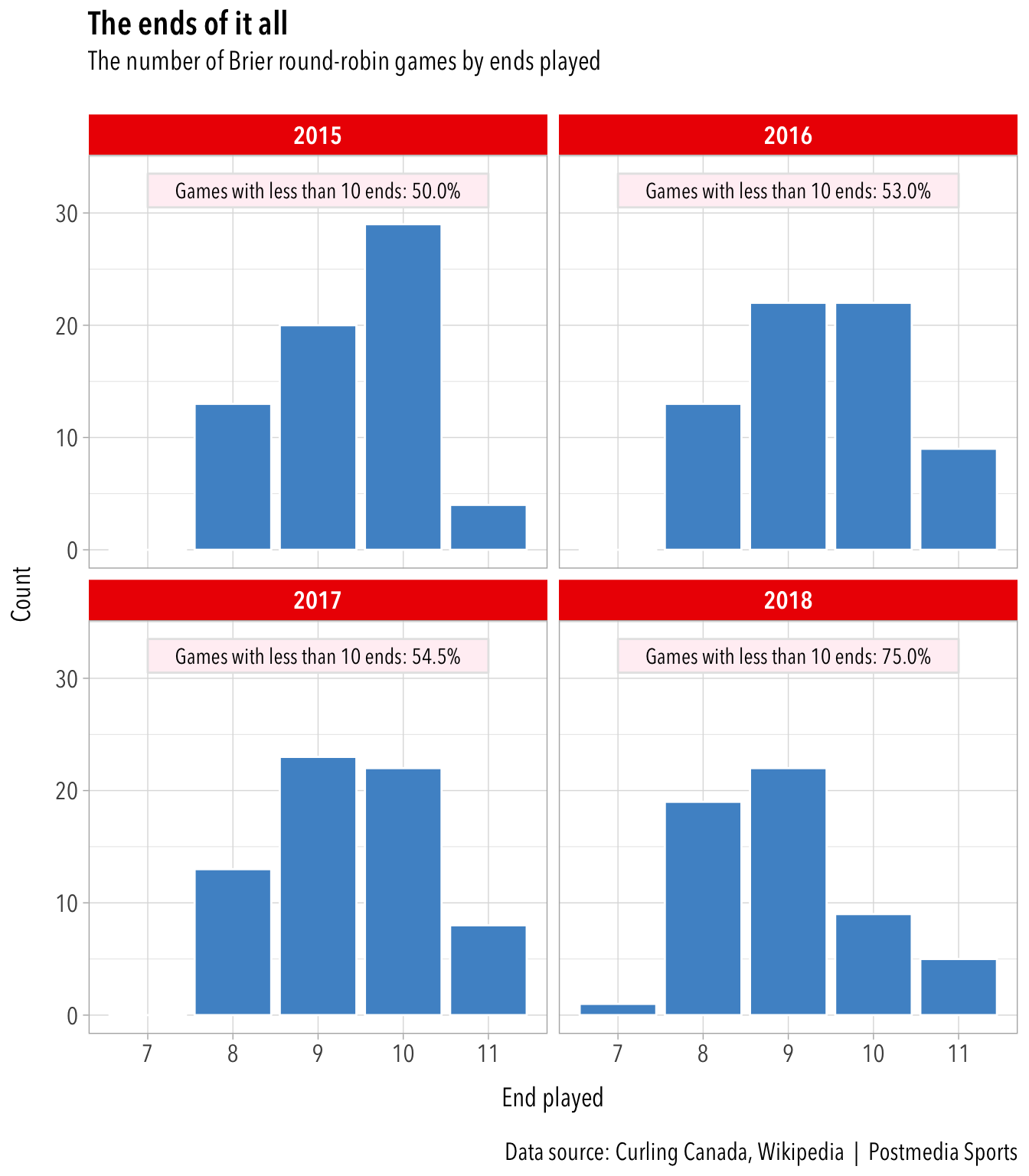

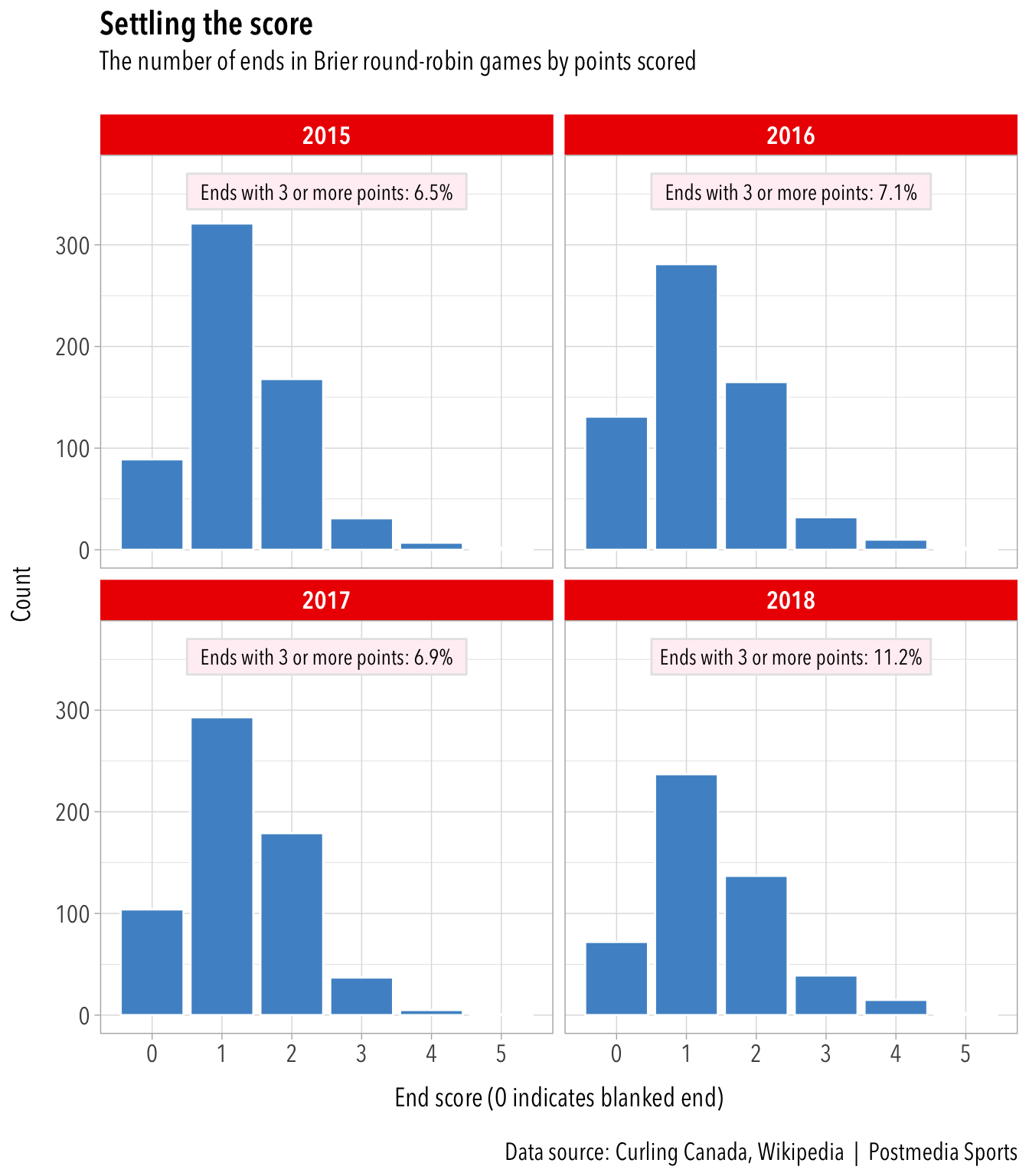

Next, let’s look at the number of ends played in the last four Briers.

There were a lot more early handshakes under the 16-team format. Just 25 per cent of games went to 10 or 11 ends, down from an average of 47.5 per cent in the past three years. More than one-third of games were called after eight ends, compared to one-fifth in 2015, 2016 and 2017. P.E.I. and Nunavut only bothered playing seven ends in their 14-2 game, which never happened elsewhere in the sample.

Strikingly, all of Nunavut’s seven losses came before the 10th end; that was also the case for five of six Yukon defeats. On the flipside, Gushue’s Team Canada didn’t play a single 10th end among its seven round-robin games because they kept winning early, save for the loss to Alberta.

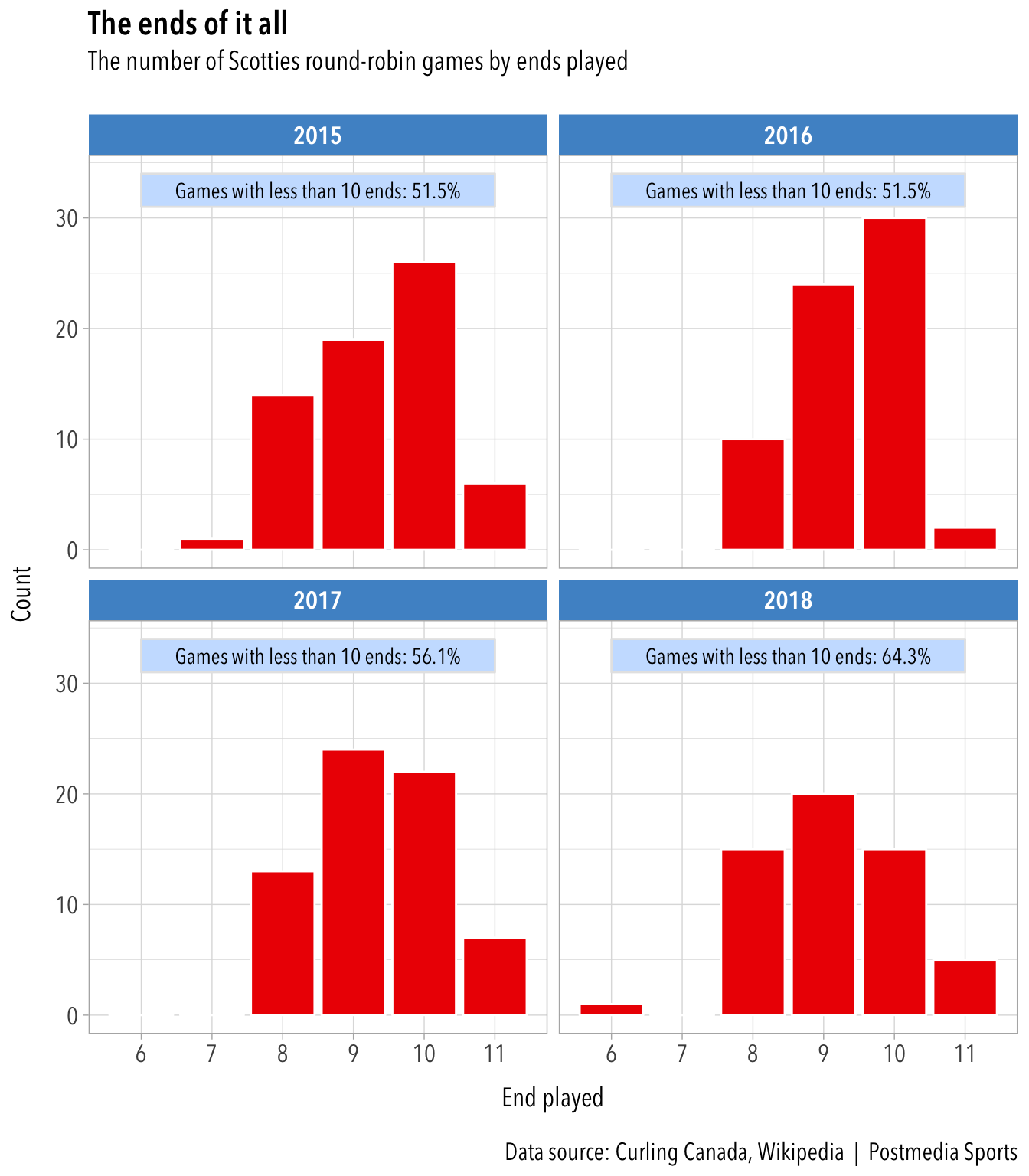

The lurch toward shorter games wasn’t as stark in the Scotties, though it was also evident: only 35.7 per cent of games went the full complement of ends, compared to an average of 47 per cent in the other three years. And 28.6 per cent went eight ends or fewer; the average from the other years was 19.2 per cent.

The usual suspects stand out here. Manitoba’s 14-1 win over Yukon concluded after six ends, and like their male counterparts a month later, Nunavut lost every game without ever appearing in a 10th end.

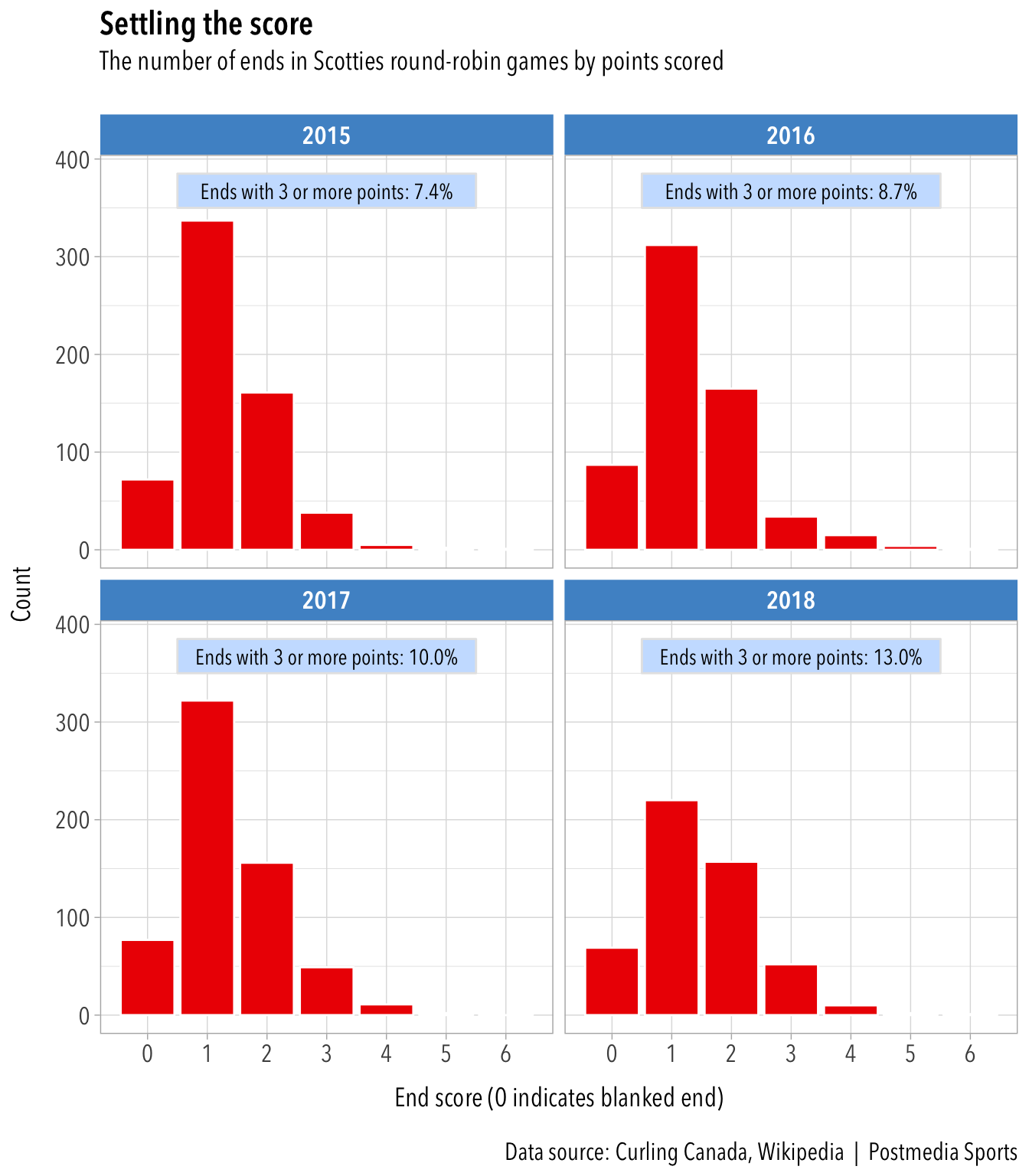

Lastly, let’s consider score by end. How often did teams tally three, four, five or even six points in one go?

The proportion of low-scoring ends — one or two points — at the Brier was in line with those of the past few years. But the percentage of blanked ends decreased. And ends in which three or more points were scored went up substantially, to 11.2 per cent this year compared to between 6.5 and 7.1 per cent in previous years.

Overall scoring totals also show how disparate the round robin was. The average points per end this year was 1.390 compared to 1.271 in 2017, 1.219 in 2016 and 1.275 in 2015. Of the 52 teams that competed at the last four Briers, five of the six highest points-per-end averages were registered this year: Ontario (0.984 points per end; ranked No. 1), Alberta (0.937, No. 2), Canada (0.932, No. 3), Manitoba (0.873, No. 4) and P.E.I. (0.790, No. 6), which finished 2-5 despite scoring a lot. On the low end, Newfoundland and Labrador was 47th (0.508), Yukon was 48th (0.500) and Nunavut was dead last (0.386).

Just like the Brier, one- or two-point ends occurred in the Scotties at roughly the same rate as past years, but blanked ends were slightly down and higher-scoring ends were up. Although there weren’t as many ends with five and six points — only three in 2018, which was equal to 2015 and fewer than in 2016 — teams scored three or more points in 13 per cent of ends; the average from the other years was only 8.7 per cent.

Average score per end was up to 1.462 at this year’s Scotties, up from 1.353 in 2017, 1.343 in 2016 and 1.313 in 2015. Six of the 10 highest average score per end among the 52 teams in these four tournaments were recorded this year. Jones’ Manitoba rink scored a whopping 1.155 points per end, followed by Alberta’s 0.952. Yukon (0.450) and Nunavut (0.404) had the lowest averages recorded in this span.

It’s difficult to say this new format ruined the national championships for viewers. The best teams still ended up in the playoffs. But there were days early in the tournament where a draw lacked a compelling matchup for TSN. It seems doubtful that Curling Canada will change the format because of the complaints of the superteams. The whole idea of the expanded tournament came from the full membership and offered an opportunity for the smaller provinces and territories to have full participation without completely clogging the event.

Perhaps it’s time to consider something entirely new: a promotion/relegation system with two pools of eight teams apiece, just like the IIHF employs for its world championships.

The bottom eight could play a full round robin and playoffs for the right to join the championship pool the next year, while the top tier would play for the title and to avoid dropping down. All the games could be held in the same location so that every team gets the full Brier or Scotties experience. The secondary pool could start on the first Friday or Saturday and finish midweek, leaving the top flight to start on Monday and carry through to Sunday’s finale.

One flaw with this format involves the wild-card team: if that entity is ever relegated, it’s unlikely any top rink that doesn’t win their provincial title would be thrilled to participate in the Brier or Scotties just to play for a shot at promotion.

But the data shows this year’s national championships overall were less competitive than in the previous three years that used the pre-qualifying event. Balancing a mandate to grow the game across the country against putting on a worthy and competitive national championship show remains a tricky task.

Originally written for Hot Buttered Post at National Post